Blazor Changes in .NET 8 - Solving Blazor's biggest challenges?

A 16 year old boy sits in his bedroom, eyes fixed on the glowing screen in front of him. The CRT monitor, as deep as it is wide, sits at a jaunty angle on one corner of the desk.

On the monitor are a series of symbols and text, combinations of characters: < > and /, interspersed with words.

The boy hits a button, stares intently at the screen, waiting for something to happen.

After a momentary pause, a broad smile forms on his face as a web page springs to life before him.

His changes worked; maybe this HTML thing wasn’t so difficult after all.

Keen to learn more, he turns back to his giant HTML reference book and considers what to try next.

Fast forward 25 years and the boy, now a man, finds himself staring at two much larger screens (which take up relatively little room on his desk) writing a blog post about the evolution of the web and a framework called Blazor…

The fundamental building blocks of the web#

Here’s the thing, if you’ve been building web pages since those early days, you’ve probably got this nagging feeling that web development used to be a lot simpler.

From the earliest days navigating the web was a fairly straightforward process involving your browser (the client) and a web server, hosted somewhere on this newfangled “World Wide Web” everyone was talking about.

To access a web page:

- You’d type a URL in your browser and hit enter

- A request was sent to a web server

- The web server located the relevant HTML page (for the specified URL) and returned a response with that HTML page’s contents

- Your browser parsed the resulting HTML, figured out how to render it and displays the resulting web page

There were a couple of other features, baked into the web from the very beginning.

You could use links to link to other web pages. If someone clicked a link their browser would kick off the process above, for the linked URL.

You could include forms on your pages. Your users could enter data into the form fields, then post that data to the web server (either as form data or serialized into the query string).

And that was it. The web was a handy way to request pages (documents), follow links to other documents and, occasionally, submit data to the server.

But as the web grew in popularity, web pages continued to evolve.

Visitors started to demand more from their browsers; they wanted more than the static pages of text and images to which they had become accustomed.

Pictures of pets, marquee tags and a “works with Netscape Navigator” badge were no longer enough to satiate the needs of the average web user.

Some limitations of the “multi page app” approach were becoming apparent.

If you entered data into a form the data would be posted back to the server, you’d be redirected back to the same, or a different page and your scroll position would be lost.

Entered invalid values? You’d find yourself bumped back up to the top of the page, and having to scroll back down to the form to discover what the error was.

NOTE

Post Redirect Get

This pattern of posting data and then being redirected is called “Post, Redirect, Get”.

When you submit a form to a web server, that server can read the form data, take action, then send a “redirect” response to the browser. The browser then fetches the URL specified in the response.

This ensures the browser history is “complete”, with entries for the original page (with the form) plus the page you were redirected to. With this you can hit the back button and get back to the original page (with the form).

Incidentally, if you ever run into a warning about “form data being re-submitted” that’s because the site hasn’t implemented Post, Redirect, Get and is instead returning new HTML directly from the POST request.

Because all interactions with the server require a POST and a full page GET, you can’t really create “dynamic” applications with this multi-page approach.

As Kent Dodds references in his excellent article on the web’s next transition, it would be sub-optimal if you smashed those “like” buttons on your social media feed only to find the entire page reloaded and shunted you back to the top of your feed.

Enter JavaScript#

So it was we found ourselves turning to an emerging technology to solve some of the web’s fundamental limitations and challenges.

With JavaScript we could make the client (the browser) a little bit smarter.

The browser could now intercept user interactions, and run logic on the client before (or indeed after) information was sent to the server.

If you ever used JavaScript (and likely JQuery) at this time you probably remember the phrase “hijacking the form”.

This was where you could write JavaScript code to intercept a form post, grab the data, send it to the server via a fetch request, then interpret the results and update the page (the DOM) based on the results.

Suddenly there was a solution to that problem of a user submitting a form and losing their scroll position.

Now they could hit the submit button, JavaScript could take care of posting the data (in the background), interpret the response, and show validation errors, all without moving the user from the page they’re looking at.

It went further than just hijacking forms; we could manipulate the DOM directly in the browser too.

Things we now take for granted, like lists where you can click a button to add a new entry, became possible.

We could do more in the client, without resorting to full page loads to get new information displayed in the UI.

NOTE

If you’re wondering where .NET fits into all this.

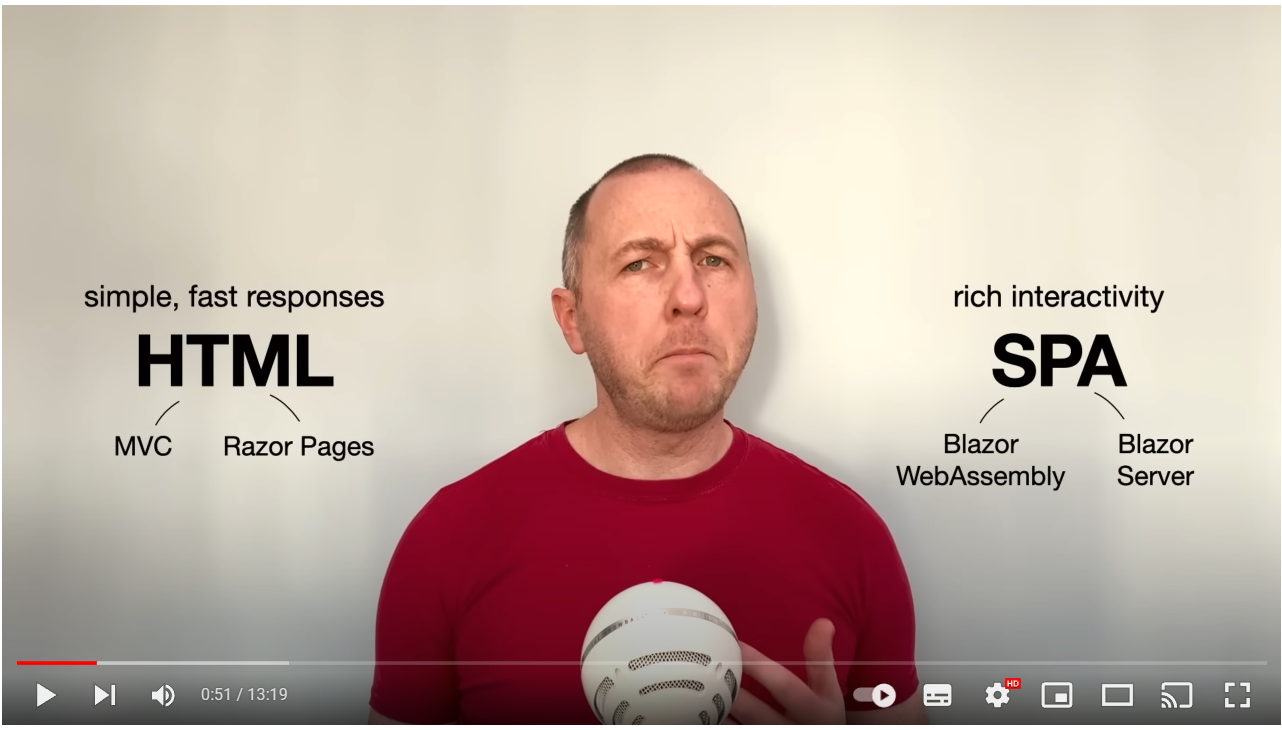

For Multi-page apps (with an option to enhance parts of the experience using JavaScript) .NET currently offers MVC and Razor Pages (and, technically, still supports WebForms),

If you’re happy to deal with full page requests, with all business logic taking place on the server and full pages being returned in the response, Razor Pages and MVC fit the bill.

OK, this is all very interesting, but what about Blazor?#

If the web had stopped evolving at that point, we’d all still be writing web sites that revolve around pages, with a little bit of JavaScript to enhance some aspects of the user experience.

But as we all know, it didn’t, and we find ourselves in the world of the Single Page Application.

SPA frameworks like Knockout, Angular, React, Vue, Svelte all take a different approach.

They essentially abandon the traditional multiple pages stored on a server approach in favour of pushing more logic to the client (the browser).

With SPAs the “flow” for accessing a web site becomes:

- You request a URL in your browser

- The server redirects the incoming URL to a single page (irrespective of which URL you requested)

- The server responds with the HTML for this single page (often index.html)

- The browser displays this HTML and loads the static files needed for the app (JavaScript, CSS etc.)

- The browser then spins up the app (JavaScript)

- From here, all interactions with the web app are via this client app (including routing, data fetching)

There’s a bit more going on here than our other examples, so let’s break it down:

Initial Load#

- Our fictional user visits the app’s home page ”/”

- The server returns a response with the contents of index.html

- The browser then fetches all the static resources referenced in index.html (JavaScript, CSS etc.)

- The browser loads the SPA in the browser

Subsequent Interactions#

- The user decides to click the link to view their profile

- The SPA intercepts the browser’s request for

/profileand, instead of sending that request to the server, locates the relevant SPA component and renders its UI - The user then updates their name and saves their changes

- The SPA posts the new profile data (as JSON) to the relevant server API endpoint

- The Server responds with

200 OK - The SPA updates the DOM to inform the user that their changes have been saved

With this model there is a bigger initial download when someone loads the app.

The browser downloads then spins up the entire app.

Once this is done, the app is generally more responsive and ‘interactive’ than a Multi-page app.

When you request a URL in the browser the SPA intercepts the request, finds the relevant piece of UI and renders it, with no need for the server to be involved.

Of course, if your UI interacts with data there is still a need to fetch data from, and post data to, a server; this is typically done using fetch requests to a backend API which accepts and returns data serialized as JSON.

The client application (SPA) can interpret JSON data responses from the server and use it to update the UI in the browser.

Struggling to figure out what to focus on with Blazor?

BlazorSharp - The .NET Web Developers community is here to help!

- Connect with your fellow .NET web developers

- Keep up to date with the latest .NET changes

- Exchange tips, tools and tactics

For a long time JavaScript and SPAs went hand in hand. If you were building a ‘modern web application’ in the form of a SPA, you were using JavaScript.

Then Microsoft released Blazor.

Come in Blazor#

Blazor enables you to build modern SPA applications, using C# and a robust component model.

Today Blazor can run in one of two possible hosting models.

Blazor Web Assembly#

Blazor apps run in the browser via Web Assembly (a technology, baked into the browser, which enables you to run code using virtually any programming language).

A Blazor WASM app loads in the browser (like other SPAs) and handles all routing and UI.

When you request a “page” in Blazor WASM, the request is handled client-side (in the browser).

Blazor intercepts the request, locates the relevant UI, and renders it.

Blazor Server#

Just to add another option to the (potentially very confusing) web framework picture, Blazor apps can also run on the server.

In this mode any interactions with the page (clicks etc) are sent to the server via a Web Socket connection.

Blazor (operating on the server) keeps track of a virtual DOM (a representation of the various elements of the current UI),

When someone interacts with a component, Blazor Server intercepts that interaction, executes the business logic associated with that interaction, then compares the new Virtual DOM with the previous one to figure out which parts of the UI have changed.

It then sends a ‘diff’ to the browser which, in turn, updates the DOM to reflect those changes.

It’s all in the components#

From a development perspective the big difference in building ‘traditional web applications’ using MVC, or Razor Pages and building ‘modern web applications’ using Blazor, lies in how you build your UI.

With Blazor you build your UI as components.

These are self contained parts of UI, with their own state and behaviour.

Greeting.razor

<h1> Hello @name</h1>@code {

string name = "Alice";

}You can render these components in other components:

<!-- Two greetings! -->

<Greeting />

<Greeting />And you can mark a component as ‘routable’, so users can navigate directly to it via its URL.

Index.razor

@page "/"

<Greeting />

<Greeting />In this example requests to the ‘root’ page of the app would render this Index component which would, in turn, render two instances of our Greeting component.

Almost, but not quite#

At this point, with .NET 7, Blazor has matured. Its API is stable and you can build rich, interactive, web applications using its component model.

But, there are trade-offs with both of the current hosting models.

With Blazor WASM, when someone accesses your site for the first time there is a sizeable initial download; a version of the .NET runtime, and your entire application are downloaded to the browser.

Even for a small application this download will be several MB in size, and results in a noticeable delay while your page loads.

On mobile devices this delay is even more pronounced.

After the initial load the .NET runtime files are cached in the users browser, but they’re still likely to experience a slight pause every time they access your app as it spins up in the browser.

With Blazor Server this problem of the initial load goes away. Because everything is running on the server there is no need for the browser to download lots of code up front.

This generally results in fast initial loads of Blazor Server apps but, they have their own trade-offs.

Now there is a need to keep a socket connection open, and to store the current state of the UI, for every user, on the server.

This means your server has to scale up as your site gets more popular.

There are also issues whereby the socket connection is dropped, and the user is shown an error requiring them to reload the app.

These trade-offs, for both Blazor WASM and Blazor Server mean there are certain sites where Blazor is a sub-optimal choice.

Not great for pages#

I had my own experience of this when I was building https://practicaldotnet.io.

The site consists of two different types of content: the “courseware” (the actual courses themselves), and a number of mostly ‘static’ landing pages.

Whilst the courseware itself requires a certain amount of interactivity, the landing pages simply need to:

- Load fast (no-one wants to click a link to find out about a course only to wait while Blazor WASM fires up)

- Be SEO friendly (so search engines index them properly)

So for those pages, we want server rendered HTML, returned to the browser as quickly as possible.

There are many sites where this kind of page is needed…

Blogs, product pages, anything with pages which are mostly static/informational, where you want the page to load fast (before the potential visitor loses interest and goes elsewhere) and interactivity isn’t a priority.

But even on these pages you might want a small amount of interactivity.

For example, my course landing pages need buttons to actually go ahead and buy the course.

This leaves us in a kind of “in-between” state, where want a combination of the following:

- Fast, responsive pages (plain HTML)

- An easy way to progressively enhance these pages (add a small degree of client-side interactivity)

- The option to go “full blown SPA” where it makes sense within our app

Currently, to achieve some combination of these three you’re going to find yourself mixing and matching technologies.

You might be using Blazor for your app (because you find its component model to be a productive way to think about, and build your web UI) but then you want some of these simpler, mainly HTML pages as well.

What do you do? Currently, you could:

- Build these simpler “pages” as Blazor components anyway, and just tolerate the Blazor WASM/Server trade-offs

- Build them as razor pages, or MVC views instead (this way everything is processed on the server and the page loads remain fast)

But what if you want a combination of the two (a fast loading page with a Blazor component or two thrown in for good measure?)

Now you’re stuck somewhere between a rock and a hard place.

It’s technically possible to build Razor Pages and use Blazor in the same app. But you have to master two frameworks (Razor Pages and Blazor) and context-switch between them.

What we really need, is a way to have our cake (Blazor) and eat it too (use it everywhere, but still have fast loading pages without the need for permanently open socket connections).

Which brings us to…

Full stack web UI with Blazor - Big changes in .NET 8#

Steve Sanderson took to YouTube recently to show an early prototype of Microsoft’s ideas for unifying these different ways of building web applications.

Steve Sanderson ponders how confusing it is to choose between the different ways of building a .NET site…

This is a significant push by Microsoft for .NET 8 to blow the doors open on Blazor’s potential as a standards based framework for building modern web applications.

In the last few years we’ve seen concerted efforts in the web development world to move towards a model which brings the interactivity of a SPA, but with the performance of a multi-page app.

Remix, a web framework which uses React as its templating engine, is one example of this; it leans on the traditional mechanisms of the web (full page responses, links, and forms) to build web sites which initially work without JavaScript, but are then enhanced by JavaScript as it becomes available.

The changes mooted for .NET 8 promise something similar for Blazor and .NET, combining the benefits of Razor page, Blazor Server and Blazor Web Assembly, all in the same app.

Server Side Rendering of Blazor Components#

The first potential improvement is an ability to build all your pages using Blazor Components.

This would mean you could create a component in your web app and have it rendered on the server.

Here’s an example of a simple Blazor component to show products:

Index.razor

@page "/"@inject IProductStore ProductStore

<h1>Products</h1>

@foreach(var product in products) { <ProductCard Product="product" />}@code {

List<Product> products;

// code to load products

}The prototype Steve demonstrates in his video includes this line in Program.cs:

app.MapRazorComponents();With this in place:

- The user requests this ‘page’ (”/”)

- .NET locates and renders the relevant Razor Component (Index.razor here)

- A full HTML page response is sent back to the browser

It’s worth raising the caveat here that this is all experimental, and these APIs are likely to change before they eventually arrive in .NET 8 or beyond.

You don’t need to load any Blazor scripts (WASM or Server) on the client, as there’s nothing “clever” happening client-side.

You get to use Blazor’s component model (including layouts, routing, validation etc.) on the server.

The server then returns HTML document responses to the browser.

The big win here is for developers who want to use Blazor, but still have fast page responses because everything is processed on the server.

There are no socket connections, no persistent state between client and server, just an HTTP GET, and HTML sent in the response.

But there is a downside to this approach.

Let’s say our component has a “Loading…” state (for when we’re still fetching data from a database).

@page "/"@inject IProductStore ProductStore

<h1>Products</h1>

@if (products == null) { <h3>Loading...</h3>}else { foreach(var product in products) { <ProductCard Product="product" /> }}The problem, if we’re rendering everything on the server, is that the user will never see the Loading… state.

Instead, they’ll make the request to the server (for the page at ”/”), the server will wait until it’s completely finished rendering (including fetching, and rendering the list of products) then return its HTML response.

So how do we make that loading state appear?

Streaming Rendering to the rescue#

MS are proposing to enable something called Streaming Server Rendering.

It is, as it sounds, the ability to stream HTML from the server to the client as it becomes available.

Essentially this technology (which is not specific to Microsoft) makes it possible to break a large bit of HTML into smaller chunks, and stream those chunks into the response object.

In effect, we can continuously send data back to the client and the client can start rendering the contents as they arrive.

In practice this means users will get the page in ‘instalments’.

They might get the “shell” of the page first (the important things that make web pages work, like body tags, and page titles), then the loading state, and finally the rendered list of products:

There’s a nice write-up about Streaming Server-side Rendering here.

In the current prototype we could enable this for our component with a single attribute:

@page "/"@inject IProductStore ProductStore@attribute [StreamRendering(true)]

<h1>Products</h1>

@if (products == null) { <h3>Loading...</h3>}else { foreach(var product in products) { <ProductCard Product="product" /> }}Progressive Enhancement is cool again#

However, if we just stick to server-rendered pages like this, we find ourselves running into some of the challenges of full page loads we saw earlier:

- If you submit a form, you’re going to lose your scroll position

- Every time you want to interact with the page you’re going to have to do a full form submission and potentially fetch a new page, following a redirect response.

To solve these challenges, MS are exploring ways to progressively enhance the UI using a little bit of JavaScript.

NOTE

The idea behind Progressive Enhancement is that a site should always work with just HTML, before you add anything else like JavaScript.

In this case, with server-side rendering of Blazor components, we can guarantee our users will get a fully functioning web page in the first instance.

But then, if it makes the user experience better, we can use JavaScript to enhance the experience (like retaining scroll positions when forms are submitted) but remain confident that the site would still work, even if the user had JavaScript disabled.

The plan is to offer a script to enable progressive enhancement, something like this:

<script src="_framework/blazor.united.js"></script>In Steve’s video, this automatically enhances navigations and form posts to make them faster and more “SPA like”.

For navigation, this tweaks things so that your browser only has to fetch the relevant HTML for the page you’re navigating to.

It doesn’t have to fetch JavaScript, CSS etc.

In effect:

- The navigation is intercepted by JavaScript, which requests the relevant HTML for that new page from the server

- The server returns just the HTML for the new page

- The browser replaces the current HTML with the new HTML

The key improvement here is that we’re not making full page requests, and sending the entire page back to the client for every single navigation.

This feels like a kind of “SPA lite” option, where we avoid performing full page refreshes but aren’t going down the path of loading an entire application in the client.

It does the same for form submissions.

I presume this is similar to the form hijacking we used to see with JavaScript and JQuery, whereby JavaScript intercepts the form submission, uses the fetch API to perform this in the background, and handles the result, all without losing scroll position or reloading the entire page.

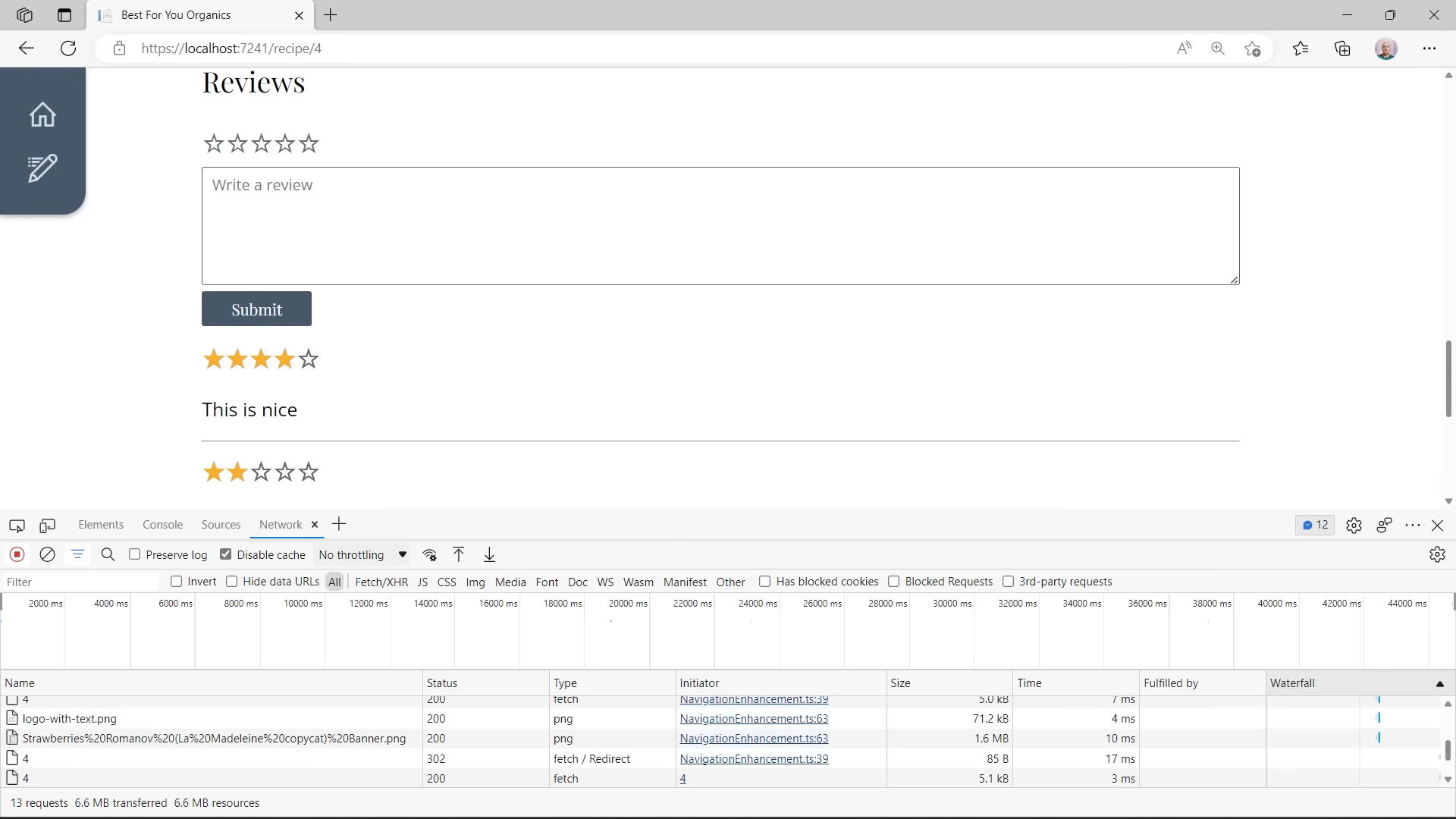

This still, from Steve’s video, shows that he hasn’t lost scroll position when submitting the form.

Notice, in the Network tab of the dev tools, that a 302 redirect response was received, and the client subsequently made a new request (to the URL referenced in that redirect request) but no full page reload occurred.

You can still go “full SPA” when you want to#

Finally, even if you choose to use server-side rendering, and progressive enhancement for most of your site, you may still want some parts of your site to be ‘more interactive’.

Maybe you have a page where you want to dynamically build up a list of items, clicking buttons to add new lines to the list, maybe delete or edit existing lines, something like this:

ToDoListEditor.razor

@foreach(var item in todoList){ <ToDoItemEditor item="item" />}<button @onclick="addItem"> Add</button>@code {

List<ToDoItem> todos = new List<ToDoItem>();

void addItem(){ todos.Add(new ToDoItem()); }

}We’re showing a list of ToDo items. If the user clicks the Add button, a new item is added to the list, which will automatically render another instance of ToDoItemEditor for the newly added item.

Now you could try to make this work using just server-side rendering and HTML forms, but Blazor is a much better fit for this kind of page.

The current proposal is to enable you to choose to use Blazor (server or WASM) for specific parts of your UI, like this To Do list component.

In the current prototype, when rendering a component like this, you can specify a renderMode:

ToDoList.razor

@page "/ToDo"

<ToDoListEditor rendermode="@WebComponentsRenderMode.Server"/>With this we’re indicating that this ToDoListEditor component should run using Blazor Server.

Now a web socket connection will be opened, but only when we hit a page that renders this instance of our ToDoListEditor.

This is a big improvement over the current situation where you have to go “all Blazor” or “no Blazor”.

Rather than keep a permanent socket connection open, this will automatically open the connection when any component on the current page requires it, then close that connection again when it’s no longer needed.

Interestingly, this can be done at the page level too (not just for individual components).

For that, the prototype supports the use of an attribute:

ToDoList.razor

@page "/ToDo"@attribute [ComponentRenderMode(WebComponentRenderMode.Server)]

<div> <h1> "To Do" List </h1> <ToDoListEditor/></div>If you want to go down the Blazor WASM route, that’s an option too:

@page "/ToDo"@attribute [ComponentRenderMode(WebComponentRenderMode.WebAssembly)]

<div> <h1> "To Do" List </h1> <ToDoListEditor/></div>In this mode, the browser will dynamically start up the Web Assembly runtime when you hit a page that needs it.

Here you get the benefits of not needing a socket connection to a server, and the entire Blazor component is running in the browser.

NOTE

Steve touches on the mechanics of making your components work on both the server and the client.

For that to actually work your Blazor components would need to be compiled twice, with one version that runs on the server, and a different version that runs in the browser.

How this will work in practice remains to be seen. In his video Steve shows the possibility of specifying multiple Target Frameworks in the projects csproj file.

Put this on the “one to watch” pile for now :)

But wait, there’s also an Auto Mode#

In a final, parting shot, Steve shows one more thing in his quick-fire demo, and that’s Auto mode.

@page "/ToDo"@attribute [ComponentRenderMode(WebComponentRenderMode.Auto)]

<div> <h1> "To Do" List </h1> <ToDoListEditor/></div>The idea behind this one is to give the instant load of Blazor Server, with the low latency of Blazor Web Assembly.

NOTE

Initial Loads? Latency?

One of the trade-offs of Blazor Server is that every interaction (button clicks for example) is sent to the server.

The server then figures out how that affects the DOM, and sends a diff back to the client.

The challenge of this approach is that there’s inevitable lag involved in sending events to the server and waiting for a response.

This latency is variable, depending on factors such as the physical distance between your users and the server.

Blazor WASM solves this by keeping all interactions on the client (in the browser), but has the trade-off of having to download and load the necessary application and framework files on the initial request.

When a user requests a page (or component) marked up to use the “Auto” render mode:

If the user’s browser has NOT already downloaded the Blazor WASM runtime and your application’s .dll files:

- A Web Socket connection will be opened

- The component (or page) will operate using Blazor Server

- The browser will download the Blazor WASM files in the background

If the user’s browser HAS already downloaded the Blazor WASM files:

- The component (or page) will operate using Blazor WASM

The result would be that your users get the instant load of Blazor Server the first time they visit your site and try to use this component.

Thereafter, when they access your site and use the component again, they’d be using Blazor WASM.

When do we get to try it?#

These proposed changes for Blazor in .NET 8 are shaping up to be a significant, possibly game-changing development for Blazor.

They look set to give us the ability to:

- Use Razor Components for all types of web app

- Adopt Server-Side Rendering for simple pages with low interactivity

- Make use of modern techniques like Streaming Rendering for fast loads from the server

- Progressively enhance sites to make navigation and form submissions smoother

- Adopt a full-blown SPA approach for parts of an app

- Use one programming model everywhere (Razor Components)

Steve is keen to note this is still at prototype stage, but with official release notes pointing to this being a focus for .NET 8 (which will arrive in November) this feels like a development well worth watching.

To get involved, ask questions and offer your thoughts, head over to the Full stack web UI with Blazor GitHub issue.

Struggling to figure out what to focus on with Blazor?

BlazorSharp - The .NET Web Developers community is here to help!

- Connect with your fellow .NET web developers

- Keep up to date with the latest .NET changes

- Exchange tips, tools and tactics