Tests are hard, LightBDD can help

You know you should be writing tests…

You know automated tests offer tremendous value…

You know (deep down) that you spend more time crossing your fingers and hoping stuff isn’t broken than you should…

So why is it you’re still inclined to focus on the production code first, and tests (if they exist at all) are an afterthought?

All friction, all the time#

The problem with writing tests is it’s often really unclear how to start writing them.

Or you find there are existing tests which seem to work, but the minute you try to change something they don’t compile, everything’s red, and the test code is so hard to decipher that the easiest option is to mark them ignored and deny all knowledge!

I was working on one of my sites the other day and ran into this exact problem.

I got a few tests up and running but every time I thought of a new edge case it felt like an awful lot of effort (and boilerplate code) to get another test written.

NOTE

Beware copy and paste

I try to avoid copying and pasting tests because it’s very easy to ignore “bad” code when you just copy it, change a couple of sentences and move on.

Tempting though it is, especially when the new test is very similar to the last one, if there’s too much code to bother writing out for a new test the chances are there’s too much code full stop!

I eventually pushed the feature live only to have to switch it off again because of all the holes I’d missed (which the tests didn’t cover).

When I stood back and looked at the tests I’d just written it was abundantly clear they were too difficult to follow and there was too much friction involved in spinning up new ones.

Then, I remembered LightBDD.

Just the right level of abstraction?#

The problem is we’re hardwired to take the easiest path.

If testing is painful, the code you end up with is hard to read and it’s difficult to add extra tests to cover different scenarios, the most likely outcome is that you’ll just stop writing tests.

But flip this around and the opposite is true.

If tests are enjoyable to write, easy to understand when you come back to them, easy to add/extend and (crucially) give you a higher level of confidence as you make changes, then you’ll want to write more of them.

Done right, tests put you in a kind of virtuous cycle where each new test increases the speed with which you can make changes because you know you won’t accidentally break existing functionality, the quality of the code you’re writing goes up because you have more time to refactor (you’re no longer spending most of your days manually testing everything) and you have more time to write more tests!

But how do we remove the friction?

You may have heard of tools like Specflow.

Specflow (and other alternatives) provide an opportunity to use more “businessy” language to describe how your application should work.

NOTE

BDD

These tools provide a way to write ‘Behaviour-driven development” tests (aka BDD).

BDD aims to bridge the gap between technical and non-technical members of a team when building software. The idea is to find a shared language that enables both sets of people to communicate about what they’re building, define how it should behave, then turn those definitions into executable specifications for the application.

The theory is that the tests are readable by real people (you know, not just us developers!)

You can write statements like this, using the “Gherkin” syntax…

Given the current total is "5"When I add "2"Then the current total should be "7"Then map those statements to methods (step definitions) in your C# code…

[Given(@"the current total is "(.*)"")]public void GivenTheCurrentTotalIs(int p0){ calculator.currentTotal = p0;}Now on the face of it this works pretty well. You can write the “boilerplate” code once (all the step definitions) and quickly compose new tests (or variations of tests) simply by writing new sentences.

But this is not a silver bullet, and I’ve seen it fall down when it comes to real-world application.

One of the problems comes with the effort required to maintain these tests.

Specflow, Fitnesse and others use a completely different language for describing specs to the one in which the code is written.

This brings its own challenges in terms of translation between the layers, and managing that translation. You often have to rely on additional tools or plugins to run the translation.

Over time, tweaking the sentences means finding the step definitions to update, or the specs break, and whilst you can get pretty good integration with your IDE, you’re still relying on another plugin/tool to manage this translation.

LightBDD offers an alternative where you can still write BDD style tests, directly in your C# code and when it comes to running them you can use standard unit testing tools like Nunit, or Xunit.

A simple LightBDD test#

Say you’ve a C# project, you can add LightBDD to it using Nuget.

You’ll also need a test framework, I tend to use Xunit so would install the relevant LightBDD package for Xunit.

dotnet add package LightBDD.XUnit2This installs the LightBDD.XUnit2 package as well as other dependencies (LightBDD.Core for example).

Now to write our first scenario we just need to create a class. It works best if we define this class as partial then have two definitions like so…

public partial class CalculatorSpecs : FeatureFixture { // implementations will go here }

public partial class CalculatorSpecs { // scenarios will go here }In the second of those definitions we can describe our scenario thus:

public partial class CalculatorSpecs{ [Scenario] public void Adding_two_numbers_should_return_total() { Runner.RunScenario( _ => Given_the_current_total_is(10m), _ => When_user_presses('+'), _ => When_user_enters(200m), _ => When_user_presses_enter(), _ => Then_the_total_should_be(210m) ); }}Note how this is pure C#.

We’re not using some text-based file which will need translating to C#, instead we’re directly referencing C# methods in the scenario.

NOTE

What’s with the _ =>?

This demonstrates something LightBDD calls ‘extended scenario format’ whereby we can use parameterized steps using the discard character and a lambda _ =>.

If you don’t need to pass values to the steps you can use a slightly simpler format.

public partial class CalculatorSpecs{ [Scenario] public void Adding_two_numbers_should_return_total() { Runner.RunScenario( Given_the_user_is_on_the_login_page, Given_the_user_enters_a_valid_login, When_the_user_clicks_login_button, Then_the_login_operation_should_be_successful ); }}Worth knowing if you don’t need to pass parameters into your steps and prefer this option (with less ceremony).

Now in the other half of the partial class you just need to create the methods you referenced in your scenario.

Jetbrains Resharper/Rider and other IDE refactoring tools make it dead easy to automatically generate the methods from the scenario definition.

public partial class CalculatorSpecs : FeatureFixture{ private void Given_the_current_total_is(decimal total) { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

private void When_user_presses(char keyChar) { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

private void When_user_enters(decimal value) { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

private void When_user_presses_enter() { throw new NotImplementedException(); }

private void Then_the_total_should_be(decimal newTotal) { throw new NotImplementedException(); }}This will now compile, but obviously we’d need to actually write the code to exercise our actual test subject (calculator in this case).

Here’s a rough stab at doing just that…

public partial class CalculatorSpecs : FeatureFixture{ private readonly Calculator _calculator;

public CalculatorSpecs() { _calculator = new Calculator(); }

private void Given_the_current_total_is(decimal total) { _calculator.Reset(total); }

private void When_user_presses(char keyChar) { _calculator.TryPerformOperation(keyChar); }

private void When_user_enters(decimal value) { _calculator.EnterValue(value); }

private void Then_the_total_should_be(decimal newTotal) { _calculator.Total.ShouldBe(newTotal); }}The nice thing is we’re never too far removed from the code.

You can use refactoring tools to rename the method in either the scenario or the implementation and the other ‘half’ is updated automatically.

NOTE

Note I’ve used Shouldly here to assert that the Total is correct.

I really like Shouldly for asserts, it reads much more naturally to me than any other approach I’ve tried.

Adding new tests is easy#

The real wins come as you start adding more test cases. Say you now wanted to test subtraction, it’s dead easy to write a new scenario.

[Scenario]public void Subtracting_should_return_correct_total(){ Runner.RunScenario( _ => Given_the_current_total_is(10m), _ => When_user_presses('-'), _ => When_user_enters(10m), _ => Then_the_total_should_be(0m) );}Here it’s less of a problem to copy and paste as you’re copying and tweaking scenarios, not implementation code.

If the calculator already exists and does what it’s supposed to do there’s a good chance this new test will pass straight away, without writing any new implementation code!

Separately you can keep an eye on your implementation code and refactor it if it starts to get a bit unwieldy.

Everybody loves a good report#

Finally, the test output is really nice too.

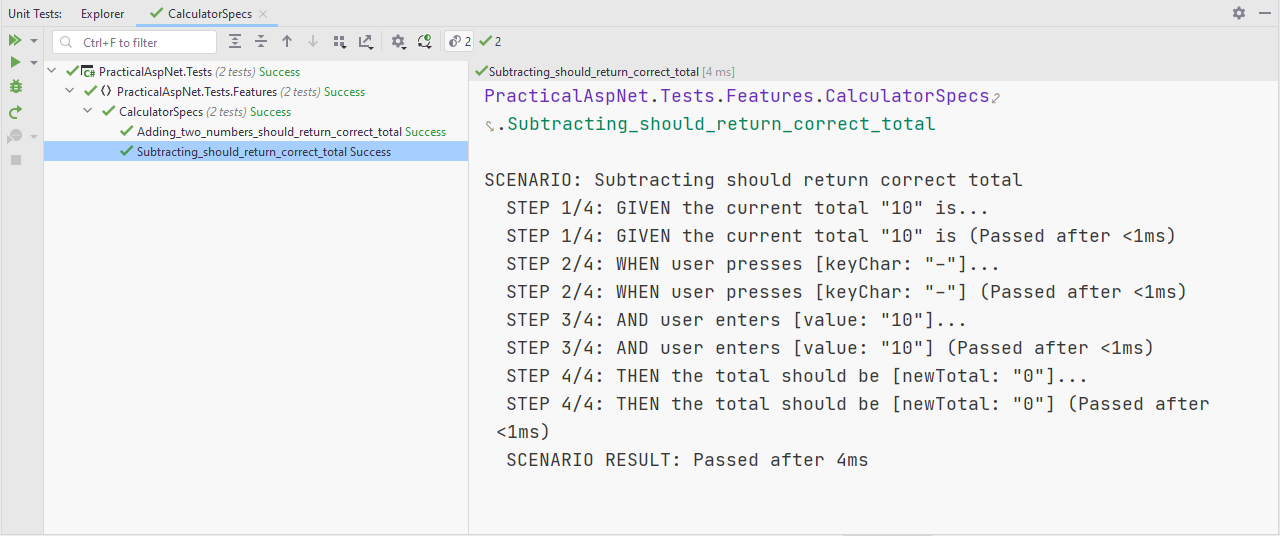

Here’s how the tests look when I run them in Jetbrains Rider…

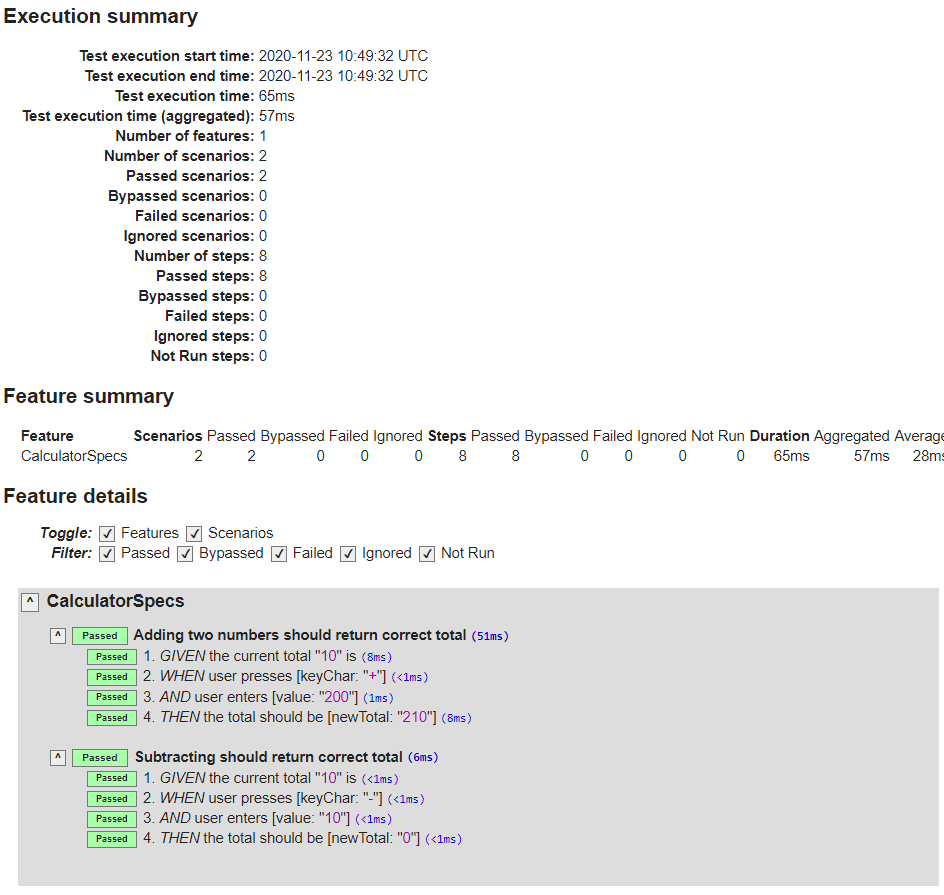

And, if you head over to the bin\Debug\netx.x\Reports folder you’ll find a handy HTML report too…

Less friction == better software#

We all know that good tests lead to better, less buggy software, and ultimately faster development.

But the sheer amount of friction involved in writing effective tests can stop you in your tracks, meaning your code fails to get the tests it deserves!

LightBDD offers a handy solution which minimises boilerplate, makes your scenarios clear but also keeps you close to your code and using your usual tools.

Struggling to figure out what to focus on with Blazor?

BlazorSharp - The .NET Web Developers community is here to help!

- Connect with your fellow .NET web developers

- Keep up to date with the latest .NET changes

- Exchange tips, tools and tactics